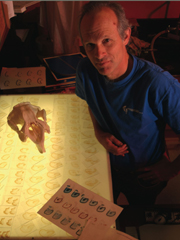

Roger Reep, Ph.D.

Professor of Physiological Sciences

College of Veterinary Medicine

2005 Awardee

While Roger Reep is studying animal physiology, he’s also making links to the same neurological disorders in humans.

While Roger Reep is studying animal physiology, he’s also making links to the same neurological disorders in humans. Reep, a professor in the Department of Physiological Sciences, has been focused on two principal areas since joining UF’s faculty in 1984: the development of a rat model of neglect, and manatee neurobiology.

In rats, Reep has worked to develop a rat model of hemispatial neglect, a cognitive neurological disorder that commonly results from right hemisphere stroke in humans. Now that he and his colleague at Northern Illinois University have developed a rat model for the disorder, they will attempt to induce neuronal sprouting.

“When the brain is damaged, nerves get killed, so we’re trying to encourage nerves that are still alive to grow new branches and take over for the ones that died,” Reep says.

Reep also leads a manatee research group, supervises graduate student research and has earned a reputation as a leader in manatee science.

“Roger has clearly been a leader in supporting a wide variety of studies of manatees,” says Charles Courtney, associate dean for research and graduate studies in the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Reep has studied the mammals for nearly two decades and coauthored the book Florida Manatee Biology and Conservation.

“What manatees are telling us about is the range of evolutionary potential because they are so weird,” he says. “They are what evolutionary biologists refer to as ‘experiments in nature.'”

One of the things his work suggests is that manatee brains are small for a good reason. As evolution played out, the manatee’s body grew, but it’s brain did not.

“It’s not that the manatees brain is relatively small, it’s that its body is relatively large,” Reep says.

Reep’s research has led to advances in the little-understood areas of manatee evolution, brain physiology and behavior, as well as implications for conservation. For example, learning about the acute sensory system manatees have within their hair follicles may indirectly help save manatees by identifying and preserving the habitat the animals need most.